TYPE-1 PLANCHET |

|

The raw stock for our clad coinage is received by the U.S. Mint from outside contractors in the form of coils. These coils are approximately 1,500 feet long, about thirteen inches wide, and weigh upwards of three tons. The process inside the mint begins when the coils are feed into machines know as blanking presses that cut out multiple coin blanks “cookie cutter” style. The machine contains a group of circular punches that are arranged in staggered rows. This arrangement reduces the amount of waste called the “web” (see example below) that is left behind. The machine first gang punches a group of blanks then automatically feeds the material forward a predetermined distance before repeating the punching operation. These two steps are repeated again and again. The resulting blanks at this point are known as “Type I Planchets.” |

|

TYPE-2 PLANCHET |

|

After cleaning and annealing there is only one other step in the forming of the planchet prior to striking. Due to the extremely high pressure it would require to raise the rim during striking, the blanks have their rims preformed. This little bit of help is what allows the coin to be struck in a single blow of the dies in a modern high-speed press. The machine that does this is called an upset mill. In the mill the blank is rolled around a continuously narrowing channel forcing the outer edge to be squeezed in, which raises a rim around the blank. When the blank emerges from the mill it’s known as a “Type II Planchet” and ready for coining.

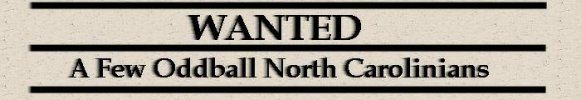

Authenticity is always a concern to the new error collector and there is one diagnostic that is helpful in authenticating an incomplete planchet is referred to as the Blakesley effect (shown left). Named for the numismatist who first noted the effect, it is a phenomenon caused during the upsetting of the rim on an incomplete planchet. Normally, as a blank is rotated and squeezed through the mill, constant high pressure is applied at opposite points around the entire planchet. This pressure is what causes the rim to be formed. However, when the missing segment of a clipped planchet rotates through the mill, the pressure on the edge opposite the clip drops significantly due to the sudden decrease in diameter and the rim is not fully raised. In many cases this is still very noticeable on the struck coin. Existence of the Blakesley effect on a clip is a good sign it is authentic, however, its absence is not reason enough alone to call it a forgery. |

|

PUNCHED QUARTER WEB |

|

Pictured here is a small piece of the waste cut out of the larger web created during the blanking process. The waste is normally chopped up and sent to be melted and recycled. The interesting thing about this piece of the web is that you can see where several of the holes left by the blanking process overlap. This would have resulted in incomplete planchets being made that when struck would become highly prized errors called "clips." |

|

SINGLE CURVED CLIP |

Click to Enlarge |

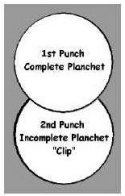

Well first, what happens when the blanking press does not advance the sheet the proper distance before the next group is punched? Too far just generates waste, but, not far enough – that’s interesting! The result is an incomplete planchet illustrated by the bottom incomplete circle in the drawing to the right. This error type has come to be commonly called a clip. This is misleading as a good planchet was not “clipped” as implied, but a defective incomplete planchet was created when the punch overlapped the area where a previous blank had already been punched. Nevertheless the name clip has persisted. Well first, what happens when the blanking press does not advance the sheet the proper distance before the next group is punched? Too far just generates waste, but, not far enough – that’s interesting! The result is an incomplete planchet illustrated by the bottom incomplete circle in the drawing to the right. This error type has come to be commonly called a clip. This is misleading as a good planchet was not “clipped” as implied, but a defective incomplete planchet was created when the punch overlapped the area where a previous blank had already been punched. Nevertheless the name clip has persisted.

The percentage “clipped” size of any of the clip types discussed on this page can be easily and accurately calculated by simply weighing the coin and subtracting the result from its normal weight. Dividing this difference by the normal weight and multiplying by 100 results in the percentage “clipped.” The only approximation required is on multiple clipped coins where this result must be distributed among the various clips. And yes, size does matter when pricing clips as the greater the percentage the rarer and, of course, the pricier! |

|

MULTIPLE CURVED CLIP |

Click to Enlarge |

Multiple clips are possible and “double curved clipped” North Carolina quarters are known. Common wisdom has it that the greater the number of clips on the coin the scarcer it is. To verify this and to give the reader an idea to the relative scarcity between types, I compiled an unscientific poll of various North Carolina pieces seen during this great quest. To date, the “double curved clip” has proven to be about five times scarcer than its “single curved clip cousin.” Although scarce, triple curved clips are encountered frequently enough to be collected, but an example on a North Carolina quarter has eluded me thus far. I have heard rumors of their existence, however, so my search continues! Although possible, quad clips and overlapping clips are very rare. As such, the discovery of one on this quest would be a major coup. |

|

STRAIGHT CLIP |

Click to Enlarge |

So, what else can go wrong? Well, what would happen if at the beginning of the coil or at the end of the coil the punches overlapped the edge? Or, what if during the production run the coil tracked to left or right enough to expose the outer end punches to the edge of the coil? The answer is a new error type – the “straight” or “straight edge” clip. In comparing the straight edge clip to the curved clip it is much scarcer. As evidence, my unofficial census of North Carolina errors has shown straight clips to be six to seven times scarcer the single curved clip. |

|

ELLIPTICAL CLIP |

Struck in Philadelphia

Click to Enlarge

Struck in Denver

Click to Enlarge |

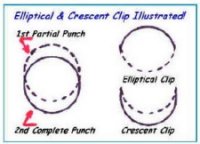

Can anything else go wrong? Yes, consider first, the punching process is stopped in mid-punch by either the operator stopping the machine or a mechanical jam. The coil under the gang punches is only partially pierced but still intact. Then, when the jam is cleared or the machine is restarted the coil is only advanced a small amount. The next set of blanks punched will have an arced cut across them from the first aborted punch. Typically, these blanks split apart during handling. The drawing to the right shows how the blank would look before and after splitting. Can anything else go wrong? Yes, consider first, the punching process is stopped in mid-punch by either the operator stopping the machine or a mechanical jam. The coil under the gang punches is only partially pierced but still intact. Then, when the jam is cleared or the machine is restarted the coil is only advanced a small amount. The next set of blanks punched will have an arced cut across them from the first aborted punch. Typically, these blanks split apart during handling. The drawing to the right shows how the blank would look before and after splitting.

Although very scarce in its own right the most frequently seen error resulting from the above scenario is the elliptical clip. Both the planchet and resulting coin have been described as looking like a football or, for those familiar with Norm Abrams on the New Yankee Workshop, a woodworker’s biscuit. |

|

DEFECTIVE CLAD LAYER |

Click to Enlarge |

The defective clad layer was added to the collection after the original exhibit completed its competitive tour. It was incorporated into the physical exhibit and shown for the first time in Wilmington at the Lower Cape Fear Coin Club Fall Show in late October 2004.

This coin exhibits thinning material with voids in the outer layers on both sides. The cause is believed to be a problem with the extruding of the layers. To my mind this would be more acceptable if only one side was affected but with both I have my doubts. I need to do more research into the process itself to fully understand what could have happened to cause this. Isn’t it funny how one discovery can lead to so many new questions? |

|

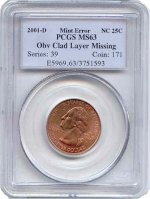

OBVERSE CLAD LAYER MISSING |

Struck in Philadelphia

Click to Enlarge

Struck in Denver

Click to Enlarge |

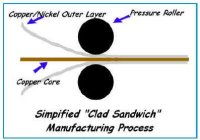

Since 1965, our "silver" coinage has been made from metallic clad material consisting of a core of pure copper sandwiched between two outer layers of copper-nickel alloy. The alloy is 75% copper mixed with 25% nickel which is the same alloy used for our nickels. As shown in the simplified drawing of the bonding process the outer layers are pressed into the copper core under tremendous pressure and heat. Although represented in the drawing as rollers the process done outside of the Mint by a contractor actually uses a controlled explosive method to insure a complete molecular bond between the three layers. Since 1965, our "silver" coinage has been made from metallic clad material consisting of a core of pure copper sandwiched between two outer layers of copper-nickel alloy. The alloy is 75% copper mixed with 25% nickel which is the same alloy used for our nickels. As shown in the simplified drawing of the bonding process the outer layers are pressed into the copper core under tremendous pressure and heat. Although represented in the drawing as rollers the process done outside of the Mint by a contractor actually uses a controlled explosive method to insure a complete molecular bond between the three layers.

The odds of which side will be struck on the pure copper side of a dual layer planchet are the same as flipping a coin - 50 / 50. This brings up a subject unique to collecting errors on statehood quarters. Dedicated collectors of statehood quarter errors have developed new terms for the obverse and reverse of their little oddballs. The reverse or state side has become the "money side" and the obverse simply the "other side." The logic behind this is the money fetched when sold can be many multiples if the statehood side instead of the Washington side is struck in the exposed copper layer! This rule holds true for any error on a statehood quarter where one side is affected and not the other.

|

|

REVERSE CLAD LAYER MISSING |

Struck in Philadelphia

Click to Enlarge

Struck in Denver

Click to Enlarge |

Due to the thinner planchet, missing clad layer coins are typically weakly struck. This however does not detract from the eye appeal or popularity of this error. The Mint's quality control process seem to be able to detect the single layer planchets better than the two layer ones as the previous is much rarer than the later. Perhaps there is a problem with the very thin single layer blanks in the rim-upset machine that helps weed them out. |

|

COMBINATION OF ERRORS |

Click to Enlarge |

Combinational errors do exist; however, are very scarce if not rare. Due to their odd shape, clipped planchets sometimes have trouble feeding properly into the striking chamber which can result in a striking error on top of the previous planchet error. One would normal be inclined to assume these combinations would be one-of-a-kind items but surprisingly, this 15% straight edge clipped planchet that was also broadstruck is one of two seen and noted during this quest. They were practically twins!

After much thought of how and where to exhibit these combinational errors, I decided that they should be exhibited under the PDS heading where the first error occurred which is how I organized the physical exhibit. However, for this e-exhibit it will be listed under both the Planchet and the Striking headings. |

|